Consequences of bad pre-slaughter handling

The hourly capital costs in running an abattoir are high and any stoppage or slowing of the line is likely to reduce efficiency and financial return. Making sure that there is a continuous supply of suitable stock on the killing floor has implications for line efficiency, meat quality and animal welfare.

Meat quality and line efficiency

When pigs fight during lairage they use their energy (muscle glycogen) and this can lead to exhaustion and DFD (dark, firm and dry) meat. Excitement, long driving races, and excessive use of the electric goad increase the pigs' energy consumption and this may affect the degree of glycogen depletion. When pigs are stressed and have no shortage of glycogen the muscles acidify at a rapid rate while the carcass is still warm. This combination can lead to the formation of PSE (pale, soft and exudative) meat, especially in specific strains of pigs.

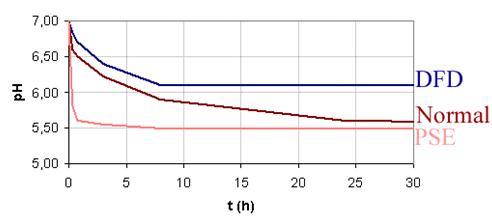

Post-mortem pH decline measured in pig muscle (Longissimus dorsi) 0-30 hours after slaughter, in PSE, normal, and DFD meat respectively. Figure: Nuria Panella.

Pork quality measured as pH and drip loss 30 hours after slaughter. Pigs developed PSE, normal meat, and DFD respectively. Photo: DMRI.

Bruising can develop when animals crush each other against doorways, sharp corners and obstacles in the driving race. Guillotine gates in races are an important cause of back bruising, and they should be padded to reduce any injury. Bruising certainly happens when pigs fall over, and this occurs frequently when pigs are moved too quickly and when they walk on wet and slippery floor. A bruise is painful and is evidence of poor animal handling. Bruising can also be found around the femur and in the leading margin of the hindleg. Not all bruises occur before the pig is slaughtered: some occur post-mortem and therefore have no welfare implications. Bruising can lead to downgrading of the carcass and sometimes the need for trimming.

This bruising in the loin has meat quality and animal welfare impact. It is a result of other pigs having pushed this pig against the ceiling in the chute during driving to stunning. Photo: Anne Algers.

When pigs are mixed into new groups, it is their natural behaviour to fight to establish a new hierarchy. When pigs are lairaged with little space allowed and without straw, they tend to fight more. Dominance aggression often results in carcass damage and has detrimental effects on meat quality, which can be presumed to compromise animal welfare.

This pig has been fighting during lairage, resulting in skin damage, and poor meat quality. Furthermore the pig is exhausted and welfare is poor. Photo: Laurits Lydehøj Hansen.

Animal welfare

Welfare problems arise when pigs are subjected to an unpredictable or uncontrollable environment. Sound driving behaviour at the abattoir is of great concern to assure a high standard of animal welfare.

Weak pigs should be handled very carefully. Very stressed animals are often taken out of the chute and left on the floor to recover. When they are capable of walking again they are sent through the chute once again. This causes unnecessary suffering and these animals should be slaughtered as soon as possible, even though this may lead to reduced meat quality.

Pre-slaughter mortality is not only an extremely serious quality problem leading to meat being condemned, it is also an indication of a serious animal welfare problem.

These pigs have died as a result of severe stress. Carcasses are condemned. Photo: Anne Algers.

Public health

Pre-slaughter stress leads to increased excretion of faeces, which will increase the risk of carcass contamination during slaughter, including contamination with food-borne pathogens.

The increased excretion of faecal material contributes to high microbial loads on bedding, floors and walls, which can in turn contaminate the skin of other animals.

Dirty pigs in lairage. Photo: Anne Algers.

Any stunning or slaughter method that involves penetration of the skin is likely to raise hygiene risks. It was found that when bacteria were inoculated on to either the bolt of the captive-bolt gun or on the blade of the sticking knife, the same bacteria could be recovered from the edible meat in the carcass.